New frontier of risk

Study finds sharp rise in opioid treatment among pregnant women

A recent study by a group of Harvard-affiliated researchers found a sharp increase in the use of opioid painkillers among a large group of pregnant women between 2000 and 2007.

The increase means that more than one in five women receiving Medicaid — which pays for 40 percent of U.S. births — took codeine, oxycodone, or another opioid sometime during their pregnancy, a troubling trend particularly because opioids have been implicated in potentially fatal birth defects in fetuses.

The research team included scientists and physicians from the Harvard School of Public Health as well as Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, both Harvard affiliates.

Rishi Desai, a Harvard Medical School research fellow working in the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics at Brigham, was the lead author. The Gazette talked to him about the research and its implications.

GAZETTE: Your study in Obstetrics and Gynecology revealed some disturbing information on medication use during pregnancy. Can you describe the findings?

DESAI: The main finding of our study was that 21.6 percent of the 1.1 million Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women included in our cohort were exposed to some kind of opioid painkiller during the duration of their pregnancy. In 2000, the overall prescription rate of these medications at any time during pregnancy was 18.5 percent. That went up to 22.8 at the end of 2007, so we saw a sharp rise in a relatively short amount of time. We need to evaluate the fetal safety of these medications because right now we have very limited information, yet their use has been increasing.

GAZETTE: Was that finding expected or unexpected?

DESAI: The magnitude was surprising, but we were expecting to see some rise because several studies have documented a similar trend in the general population. What goes on in the general population is pretty much reflective of any specific subpopulation you study, and pregnant women were our subpopulation of interest.

GAZETTE: Can you tell us a little bit about the medication itself? What is an opioid? What do we know about them and their potential impact on fetuses?

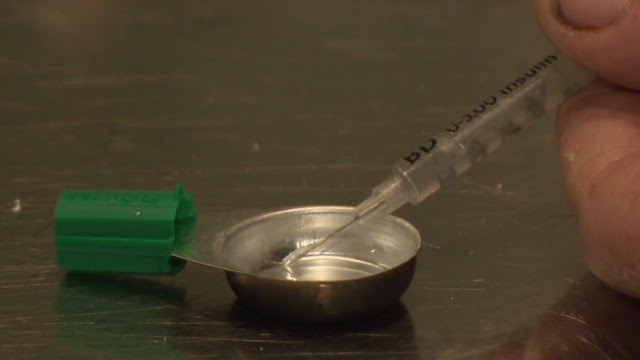

DESAI: Opioids have been around for a long time. These are painkilling medications such as codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone. There are many, but those are the ones that are more commonly used. These are controlled substances, which means the FDA has recognized them as being potentially habit-forming. These agents are basically used for pain control in the general population. Pregnancy is one of the conditions in which pain complaints are fairly common, especially back pain and abdominal pain.

One of the reasons we decided to do this study was research published in 2013 that highlighted concerns about the safety of the fetus when this medication is used. That study saw an increase in neural-tube defects in fetuses exposed to these medications in the first trimester. Another study in 2011 saw similar signals. So that signal has been replicated twice — both times in observational settings, so it’s an association and not causation, but it’s the same signal in two different studies. We were interested in looking at this from a public-health point of view. How many potential fetuses are we talking about?

GAZETTE: What is a neural-tube defect?

DESAI: The CNS [central nervous system] organs, brain and spinal cord, are formed from the neural tube in a developing fetus during the first trimester of pregnancy. Any malfunction in this process results in incomplete development of the CNS, which is potentially fatal for a newborn. It’s a very serious condition. The absolute risk of neural-tube defects is small, but the earlier studies reported doubling of this risk after first-trimester opioid exposure compared to non-exposure.

GAZETTE: You saw a 4 percent increase in use of opioids among pregnant women during the study period. Is there an epidemic of pain among pregnant women or is something else going on? What’s driving this?

DESAI: It is difficult to attribute this trend to any single factor. Obviously, there’s more recognition of pain and the need to control pain overall. Increase in the use of these agents in the general population has been well documented in various studies in the past. Our study was based on prescribing and dispensing data, so we don’t have any idea how big a factor abuse is. Our data represent filled prescriptions of opioids, so we are viewing this use as medicinal in nature.

GAZETTE: The study shows regional differences. Can you address that?

DESAI: We did see some sizable differences across states and regions. The South had the highest and the Northeast had the lowest. That could be due to a combination of several things. Underlying prevalence of pain conditions might be different in different regions and practice patterns of the physicians themselves might be different. We do know from past research that there is a huge regional variation when it comes to prescription medication [patterns].

GAZETTE: Do you have any words of wisdom for a woman who is pregnant and considering getting a prescription for some of these compounds?

DESAI: Absolutely. There has to be a discussion around the risk-benefit profile of any medication you use. If the pain is not so severe, I think physical therapy or [another alternative] could help. We are not saying these agents should not be used at all. For instance, with cancer pain or serious joint pain, these agents do work. We know that. It would be best to at least have a discussion with your physician whenever you are thinking of getting medication for your pain.

GAZETTE: What next steps are important?

DESAI: We are in the process of looking at various safety signals among fetuses after exposure to opioid agents, so I think that is the next step. This is really important and an active area of investigation. We hope to contribute more to it.